Venice. Biennale.

As the Venice Biennale soon comes to a close on November 24, we want to showcase artist, Mandy Morrison’s reflections and take on the Biennale and its Venetian environment: a paradox of place and commerce.

Mandy Morrison: Venice

This past July, I went to the Venice Biennale, the global art event, often absurdly compared to the Olympics. Occurring every two years, the theme for this year’s Biennale was Foreigners’ Everywhere curated by Adriano Perdrosa, Artistic Director of the Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand. The focus is on marginalized populations, largely referring to developing areas of the globe as well as artists with orientations or identities that have been historically marginalized.

Foreigners Everywhere, with a serious nod to global patterns of migration, easily describes Venice in high season - where the only locals are vendors of the tourist trade running restaurants, cafés, shops, museums and transport. Arriving at Marco Polo airport at 2am due to the inefficiencies of a budget airline, the water taxi into Venice - even at this unseemly hour was nonetheless breathtakingly magical as the city was dimly lit, wholly absent of people and deliciously quiet.

Guerreiro do Divino Amor, (filmmaker) born in Switzerland, raised in France — lives and works in Brazil.

Yet seeing the hoards that greeted the next day was a startling jolt and a reminder that any place – even one so historically rich and noble - is vulnerable to becoming an artifact.

When I finally made it to the Giardini (the original site of the Biennale at its inception), attendance was modest. This being July, the art world heavies had already come and done their bidding.

What is easily understood about the historic aspects of the Giardini is the placement of the pavilions themselves, both their size and how they are situated. With the lingering scent of Empire, the U.K., French and German pavilions, all built between 1909 and 1912 are adjacent to one another. The Israeli Pavilion, a modernist structure built in 1952, abuts its geo-political protector, the United States whose neoclassical - Greek-style - pavilion was built in 1930 (the Israeli pavilion was closed awaiting a cease-fire).

Yuko Mohri, born in Kanagawa, Japan. Lives and works in Tokyo.

The entrance to the Padiglione Centrale (the main exhibition hall) at the Giardini, surprises and stuns with a glorious mural painted by MAHKU, a group of indigenous artists from Brazil. It’s riotously colored narrative, depicts the mythic story of kapewë pukeni (the alligator bridge) describing the passage between the Asian and American continents through the Bering Strait.

Inside the Padiglione Centrale, as well as at the Arsenale, are a variety of curated exhibition areas and rooms. Much of what is on display exists as a survey of varying works from the artists of many parts of Africa, the Caribbean, Asia and the Global south. Often echoing the works of significant Western art movements, much of this work has been created by less familiar (to the West) artists, and is being seen in Europe for the first time.

Guerreiro do Divino Amor

Rosa Elena Curruchich, was a Maya Kaqchikel visual artist who was born in San Juan Comalapa, Guatemala. D. 2005.

Of the many rooms I visited, the modest figurative works by Sénèque Obin (1893–1977, Haiti) and Rosa Elena Curruchich (1958-2005, Guatemala) spiked my interest the most.

With rich color, attention to detail and intimate depictions of daily life’s activities and rituals within their respective cultures, one is brought into visual relationship with environments that one might not otherwise come to know.

Having three days - as I did - is barely enough time to take in the range and variety of what is on offer, especially when one considers the site of the Arsenale (at another location, separate from the Giardini). A former navel shipbuilding arena, it boasts soaring ceiling heights with exhibit halls that are long and cavernous. This is where the most recent participant countries to the Biennale are located (albeit China, Malta and Cameroon to name a few).

Sénèque Obin, Haiti. 1893–1977

So it is hard not to notice throughout the many exhibits in the halls and pavilions what the varying counties were willing to spend on the art in their spaces. No surprise then that many culturally marginalized artists who are indigenous, immigrants or first generation citizens in their adopted countries often had lavish budgets to work with (France, Switzerland, Germany, the UK). And some are well-worth spending time on. The Swiss pavilion, by Swiss-Brazilian artist Guerreiro do Divino Amor, especially caught my eye, with its over-the-top array of videos, installations and sculptural pieces that make relentless fun of Switzerland’s chauvinistic world-view as well as its own self-representation.

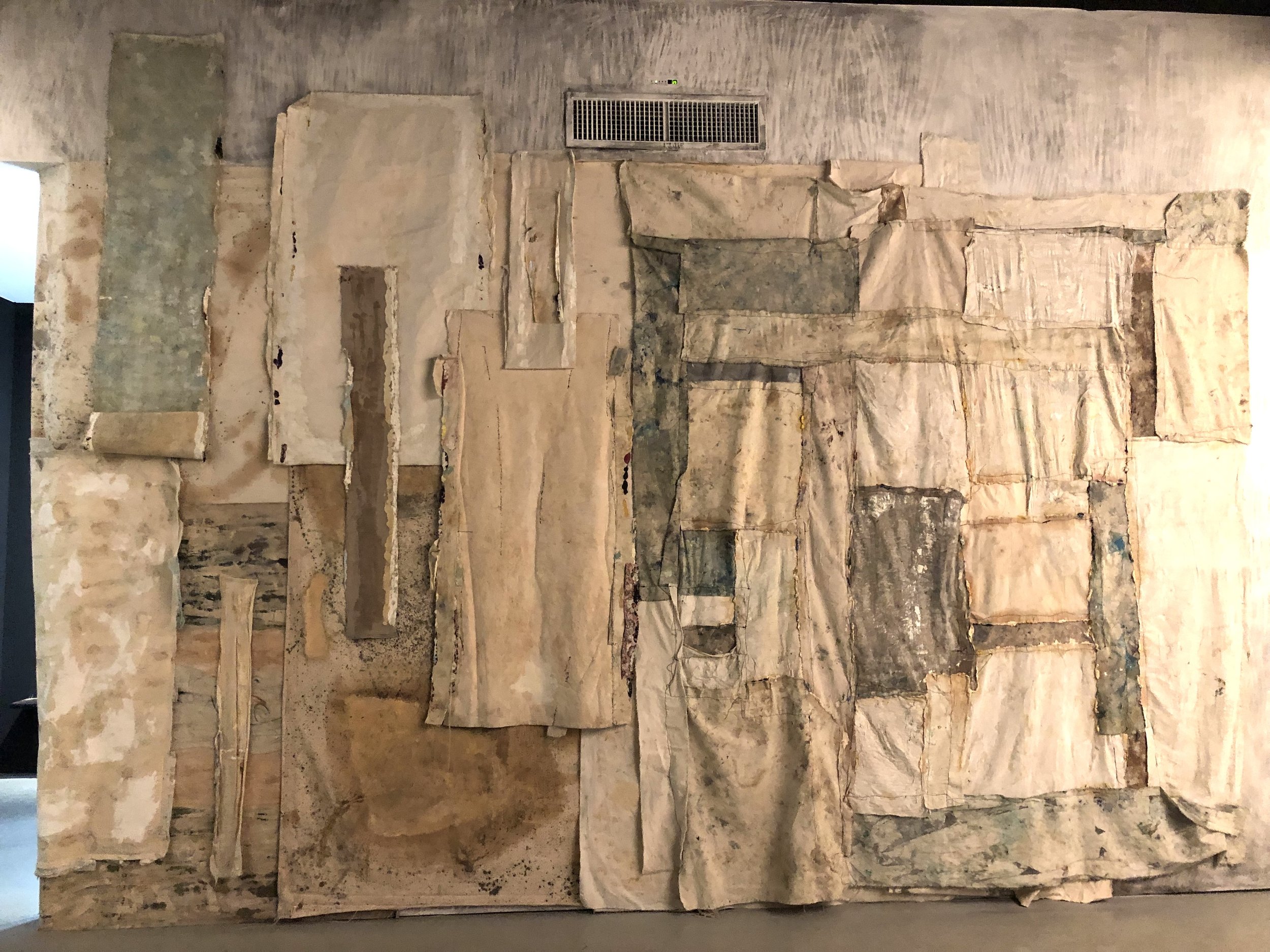

This in stark contrast to the pavilions of countries, which are far less affluent, and while movingly thoughtful, had significantly less to work with (Eduardo Cardozo, of Uruguay)

Eduardo Cardozo, Uruguay

Refreshing was the installation of Japanese artist Yuko Mohri, whose work Moré More (Leaky) relies on common household goods and everyday objects, to a create a lively kinetic Rube Goldberg-type work that generates movement and sound through the transport of water and the decomposition of fruits (through the insertion of electrodes into the fruits) converting their moisture into electric signals.

The familiarity of everyday objects with the inventive use of simple motion and a lightness of touch, grounds the work in the common everyday world; one in which most of us - in one form or another - have to contend.

One can see varying walk-throughs of the Venice Biennale on YouTube - which while not ideal - gives a snapshot view of the scope and range of what is on display.

Mandy Morrison

The Venice Biennial runs through November 24, 2024

UPCOMING: Essays and Interviews

Part II of Interview with Elke Luyten.

Interview with Anna Sang Park

Interview with Coder/Herbologist/Film Ace, Artist and Poet, Meredith Finkelstein

Essay on the work of Francine Hunter McGivern by Carter Ratcliffe

Keith Donovan new work in Montmorillon, France

PEAT and REPEAT BOOK SERIES:

Peat and Repeat is excited to announce that we are creating an artist book series that will include programming and workshop endeavors. We are launching a fundraising initiative for this series. More on this soon.

We really do rely on tax-deductible donations to keep going! The more we can fundraise the more projects in the community we can produce and our intention is to expand our community outreach.

Caterina Verde’s, Mole Mansions will be the first to emerge from this series. Expected due date December 2024